maozhang.net

Book review

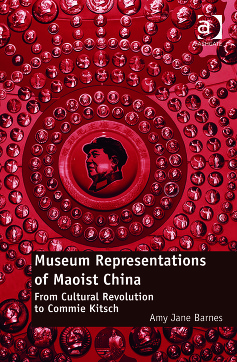

Do not be misled by the cover. This is not a book about 21st-century Chinese museums where Mao badges are used as tesserae in bright, red and shiny mosaics; this is a book about British museums and galleries, and their developing approaches and attitudes to overtly political visual culture.

For the quarter century following 1949, British museums and galleries pretty much ignored the visual and material culture of the PRC. In the first part of this fascinating book, the author traces the various reasons for this including: chinoiserie, Orientalism, the received art-historic view that Chinese art ended with the empire, contradictory assessments of Chinese civilization as either wise and refined or primitive and barbaric, and mainland China's status as part of the fearsome and newly created Other - the Communist Bloc. Unlike Lenin's Russian Revolution, Mao's Chinese Revolution did not embrace the avant-garde; there was no Chinese Constructivism or Supremacism, there was just crude derivative propaganda. Public perceptions of China were largely but vaguely negative because there was no reason for them to be otherwise - what happened behind the bamboo curtain stayed behind the bamboo curtain.

In the mid-1960s, at the height of Britain's own post-war cultural revolution when London was the swinging capital of the world, Mao unleashed his Red Guards and a flood of Little Red Books. China was pushed more firmly into the public eye with the sacking of the British Legation in Beijing and riots in Hong Kong, and opinions about China became polarized. The Establishment was resolutely anti-, but among the alphabet soup of the new left Mao was quoted as often as Marx or Marcuse; and a few smiling peasants and determined workers were stuck alongside black-light psychedelia on student walls.

The British public had to wait until 1974 for its first real taste of modern Chinese art, when the travelling exhibition of Peasant Paintings from Hu County, Shenshi Province, China made a brief tour with two residencies in London; and it is in the chapter about the exhibition, describing the interplay of policies foreign and domestic, institutional aspirations, artistic judgments, and the physical complexities of scheduling, that the author - a museum researcher and curator - really hits her stride. Public and critical reaction to the exhibition was mixed the paintings were naïve, colourful, idealized, it was just socialist realism and the woodcuts were obviously derived from European expressionism, it was propagandist, it was people's art. The main point was, however, little noticed at the time; this was a visiting exhibition, British collections contained nothing like it. Whether this was an artistic gap or not was moot - but the gap in our collectively stored physical memory had become glaringly obvious.

From the end of the 1970s, three key institutions in London began to collect Maoist material. The Polytechnic of Central London (now the University of Westminster) collected posters as teaching aids; the Victoria and Albert Museum, under the direction of Roy Strong, began to "collect the modern", while still giving primacy to aesthetic qualities; and the British Museum, as "universal museum" and depository of last resort, encouraged its curators to collect the contemporary in the field. But collecting is only the first half of the Poetic; a collection isn't a collection until it is displayed.

Having given the reader sufficient background to follow her narrative, the author proceeds to a detailed and highly informative account and critique of what, why and how these institutions have acquired; and what, why and how it has been displayed. Their acquisition and display strategies are discussed in the context of subsequent developments that have impacted our views about China - the CCP's repudiation of the "cultural revolution" as ten years of catastrophe, the growth and popularity of scar literature, the June 4th "incident" in Tiananmen Square, the return of Hong Kong, the emergence of China as an economic superpower, the Beijing Olympics, and the ironic appropriation of Maoist style and imagery by manufacturers and advertisers.

The University of Westminster collection began with a 1977 donation of 30 or so posters from a member of (the then Polytechnic) staff, and has steadily grown through gifts and purchases. As prices for the more aggressively revolutionary posters have increased dramatically, the collection has tended to concentrate on those that depict the role of women and children. Posters from the collection were first exhibited to the public in 1979 and most recently in 2011; and were the subject of an excellent and much-cited book, Picturing Power in the People's Republic of China.

The Victoria and Albert Museum had to play catch-up and at first, in the words of one former assistant curator, they collected anything "we could get our hands on". What they accumulated mainly political "stuff", and this was problematical for an institution whose philosophy was to bring aesthetics to the fore. In 1991, when the museum opened its new Chinese gallery sponsored by Hong Kong entrepreneur Xu Zhantang, the structuring of the displays had no place for potentially contentious Maoist material. A few pieces, two mugs and nine porcelain Maozhang, did subsequently find their way into the Twentieth Century Design Gallery; and while their political content could not be ignored - they showed Mao's portrait and an appropriate quotation from his Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art - their restrained whiteness was hardly representative.

The British Museum, with its remit to collect human history, gradually built up a collection that included prints, posters, textiles, ceramics and Maozhang. There was no shortage of material; the issue was how to display it. In 2008 the museum staged Icons of Revolution, the best and most comprehensive exhibition about the Cultural Revolution so far offered to the British public. In stark contrast to the decontextualized objects displayed at the V&A, Icons of Revolution was all about context; badges, banknotes, figurines, photographs, pictures and even radio schedules were situated within an explanatory framework that gave the visitor a coherent account of the Cultural Revolution and the visual symbols that were deployed.

In an epilogue, the author notes approvingly that since 2008 the display of Maoist material has to some extent entered the museum mainstream in Britain. We've come a long way since the 1950s, but we still have a long way to go especially in view of the reappraisals of Mao and his Cultural Revolution by a new generation of historians.

The whole text, and especially the latter half, is illuminated by the author's familiarity with and enthusiasm for her subject and benefits enormously from conversations and correspondence between the author and some of the "major players" in the field. For the outsider there are some fascinating behind-the-scenes insights into the poetics of institutional collection and display. I very much enjoyed this well-written and highly informative book, and have no hesitation in recommending it to anyone with an interest in the display of contemporary culture and history.

I would have liked there to be more illustrations; but isn't that always the case? And I really hope the story is true that a copy of the iconic Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan found its way to the Vatican where it was misidentified and hung in a gallery alongside Catholic missionaries - it just goes to show how appearance can be deceiving unless the viewer fully understands what is being shown.

CT