maozhang.net

Sent-down Youth

Issued by the revolutionary committee of Wuhu sometime in 1969, this badge was almost certainly intended as a going-away gift presented to the city's sent-down youth. Beneath Mao's portrait, against a vista of a wide ploughed field flanked by power lines (rural electrification) and ears of grain (the raison d'etre of the countryside) is the inscription, "Facing the countryside"; a phrase Mao wrote down in an entirely different context (with regard to art and literature), which was subsequently appropriated for the encouragement of the educated youth.

48mm 8.6g

"It is absolutely necessary for educated young people to go to the countryside to be re-educated by the poor and lower-middle peasants. Cadres and other city people should be persuaded to send their sons and daughters who have finished junior or senior middle school, college, or university to the countryside." 22nd December 1968

Towards the end of 1968 Mao decided that the student Red Guards, which he had unleashed upon China two years earlier, had outlived their usefulness. Forbidden from further revolutionary activity, these youthful activists presented a considerable social and economic problem: there were no places for them in the newly re-opened schools and colleges, and there were not enough urban jobs to go around. As the country struggled to get back to some kind of order, the presence in the cities of masses of unemployed and discontented youth presented a serious threat to that order. Mao's solution was pragmatic - disperse them to remote rural areas where they could do little harm and might actually be useful.

The concept of urban high-school graduates going to work and settle in the countryside was part of Mao's voluntaristic utopian vision. The realisation began in the mid-1950s with small groups organised locally on an ad hoc basis. There was nothing voluntary about the relocation programme that got under way in 1969. Over the next 12 years some 17 million young people were sent down to the countryside, either to work directly on the land or in rural workshops and factories. Some adapted well to rural life, but most did not. The peasants were often less than welcoming and sometimes hostile to the newcomers; physical abuse was not infrequent. The disenchanted recollections of sent-down youth subsequently formed the basis for the so-called "scar literature" that flourished in the mid-1980s.

The educated youth were not entirely sent down and forgotten. Special "Rural Youth" editions of books were published including, somewhat ironically, this world atlas that showed them all the places they could be if they were not stuck in the countryside. The volume also included a province-by-province guide to China so that they could learn at least a little about their new homes.

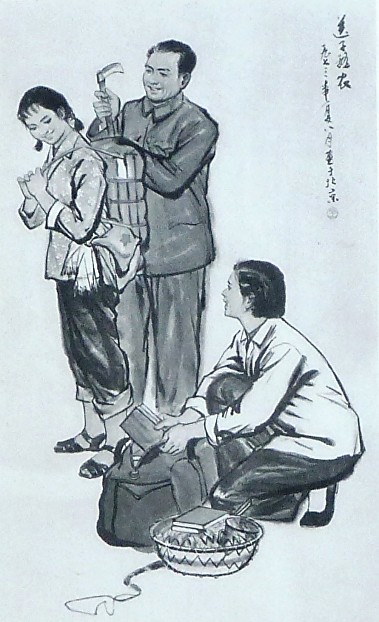

This painting, Send the Child to Farming, was shown in the 1973 National Chinese Painting Exhibition and portrays an idealised view of loving parents, the father a PLA-man, helping their daughter pack for her journey to a new life in the countryside.

See also: Mangoes 3