maozhang.net

Textile

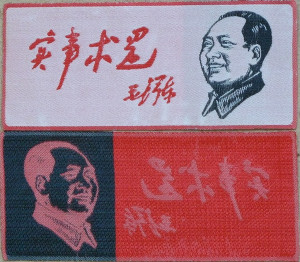

This finely woven piece of cloth was obtained in Hong Kong, sometime 1973-93.

In contrast to Europe and North America, where embroidered and woven cloth emblems (particularly butterflies) were widely used to decorate and "hippify" the jeans and jackets of late-60s early-70s youth, cloth patches do not seem to have been "mobilized" in China during the Cultural Revolution. There are several possible reasons for this: the PLA made little use of sewn-on insignia apart from officers' collar tabs; there was no other pre-existing "model" for the use of cloth patches (such as the post-WWII Hell's Angels-type motorcycle gangs in the USA); that machinery capable of making such small pieces was not widely available; and there may have been regulations/social taboos against sewing, as opposed to pinning, "statements" to clothing.

Nevertheless, the main reason for including this piece, and to slightly bending the definition of Maozhang, is to lavish praise on a book recently published in paperback: Global Textile Encounters (Oxbow Books 2014). It is a rare delight these days to encounter a scholarly tome that is adequately illustrated; with 240 images, mostly in colour, spread across 300 pages this book more than makes the grade.

Although published as volume 20 of the Ancient Textile Series, the 31 essays in the book range in time from antiquity to the latter part of the 20th century; and while most of the contents are beyond my competence to review - not my period - there is one contribution that falls squarely within it. Michael Langkjaer's From Cool to Un-cool to Re-cool: Nehru and Mao Tunics in the Sixties is a very welcome contribution to the literature.

Bizarrely chosen by London's Victoria &Albert Museum as an icon of Cold War Modern, despite the fact the design is no more "Cold War" than a pair of Levi Strauss' 1873 denim jeans, the Mao suit has received far too little serious attention. Unlike Mao's Little Red Book, which physically penetrated Western societies, the Mao suit was largely a conceptual penetration. Very few Europeans or Americans would have seen a "real" Mao suit - far, far fewer than those who owned a copy of the Quotations - but most of them would have recognised the phrase.

There are some fascinating details. I did not know that Lenny Bruce took to wearing a Mao-type suit during his performances; and the page from a 1957 pattern book showing how to cut a Mao suit from a traditional long robe is particularly interesting - although it raises questions such as, how many Chinese were still wearing long robes in 1957? The pictures and text on the reverse of the illustrated pattern book page (showing through the low-quality 1950s paper) also look interesting, and one can only hope that the private collector who owns it might make this fascinating material available to a wider audience.

h. 43mm w. 103mm

I would have liked to see the Mao/Nehru fashion influence linked to the wider mid-60s "tieless" trend that got Lord Snowdon refused service at a "top Mayfair restaurant" and resulted in the short-lived craze for collarless "granddad shirts". But this is nitpicking - anyone who is interested in the history of textiles and/or clothing will find something worthwhile in this excellent book - full marks to the editors and to Oxbow Books on this one.